Michelle Gil-Montero

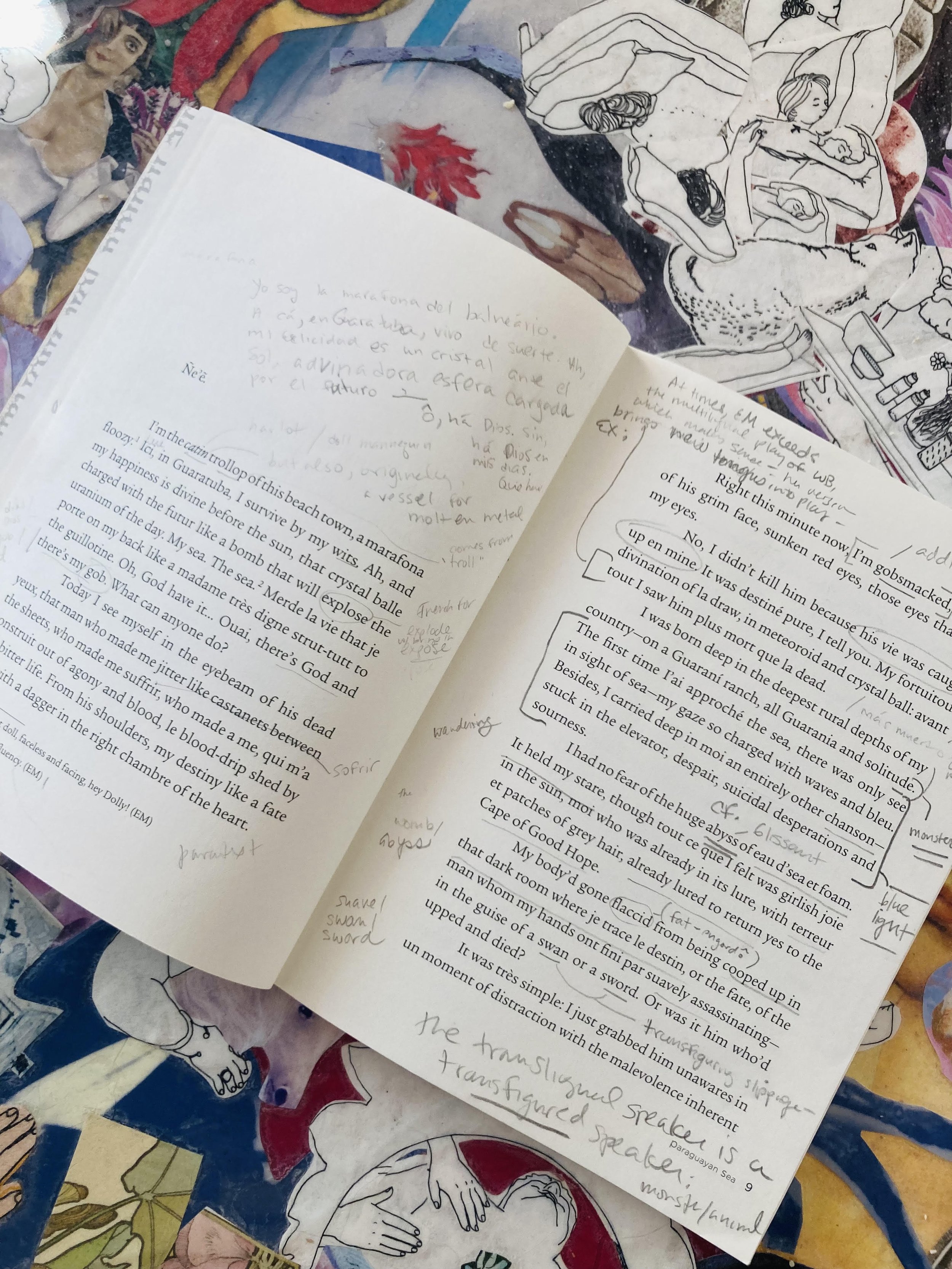

“Marginalia across whole pages of Paraguayan Sea (on my kitchen table).”

Readings

A book of poetry that was important to you when you were starting out as a poet and how has that shifted or remained constant for you over time

Lorine Niedecker, The Granite Pail: The Selected Poems, ed. Cid Corman (Gnomon Press, 1985, 1996)

This selected edition introduced me to Niedecker’s poetry, which was revelatory for me—and still is. I was a student, perplexed by that mandate to “find my voice.” In her work, I realized that it didn’t have to be a speaking voice; it could be a listening voice. A poem could be more than a podium for elocution; it could be more like a resonance chamber, full of sounds that bounce, distort, deviate wildly from the speaker’s persona and drive to communicate.

I fell in love with her compression, its musical intricacy most of all. Over the years, I’ve come to view her compression paradoxically, as sonic excess rather than verbal restraint. Her short lines are an overload of input, like musical distortion, with its warm, loud, gritty effects. In my own work, I try to bring words a little too close to the amplifiers, to let sounds drown out the single, centralizing voice.

My first love in this book was the sequential, autobiographical poem “Paean to Place”—in great part because of how sounds take over and “flood out” the speaker. For example:

I mourn her not hearing canvasbacks

their blast-off rise

from the water

Not hearing sora

rails’s sweet

spoon-tapped waterglass-

descending scale-

tear-drop-tittle

Did she giggle

as a girl?

That sora rail’s call, spilling its syllables—which channel the statement through time, from mourning into the possibility of her mother as a giggling girl. Throughout this poem, the sounds of words reroute, wash over, even silence their speaker. It makes sense to me that Niedecker didn’t like to give public readings—her poems don’t speak with one person’s voice. She noted that "a person conscious of a listening audience would write just a tiny bit differently." I remain fixated on Niedecker’s tiny bit of difference from that other kind of poet.

A poet or book in translation or in another language

Alejandra Pizarnik, A Musical Hell, trans. Yvette Siegert (New Directions, 2013)

A Musical Hell, translated by Yvette Siegert, was Alejandra Pizarnik’s first book to appear in English. I have a long, furious, almost adolescent passion for this book, both in Spanish and English. When the translation was first published, I was shocked, but also not, by its critical reception. Some reviewers found “Ms. Pizarnik” solipsistic, sentimental. There was an annoying tendency to read her poetry through the lens of her biography. Inexplicably, this child of Rimbaud and Lautréamont was dubbed “the Sylvia Plath” of Argentina. It was a case of translation coming in and revealing limitations in the receiving literary scene. And ultimately stretching it.

I love the maximalism of these prose poems, their emotional intensities, imagistic extravagances (“dolls gutted by my worn doll hands,” “the night made of wolf fangs”). Their symbolism (angels, gardens, silence, the night) that refuses to be totalized, unified. Poetry is a musical hell, and this book is a fearful descent into its circles. I read this book, sometimes, for its poetics of fear—for fear’s expressive possibilities.

Pizarnik alerts me to my own fear, the ways I hide behind language, the ways my efforts bring me back to the same place I started. It reminds me of a fear that is, I think, primal to any desire to write poetry. Pizarnik gives me fear the way someone might give someone courage. “I want you to look through the window and tell me what you see: inconclusive gestures, illusory objects, failed shapes. [. . .] Go to the window as if you’d been preparing for this your entire life.”

A book in which you were interested by the use of language or form

Wilson Bueno, Paraguayan Sea, trans. Erín Moure (Nightboat, 2017)

This is a book written in the languages of Portunhol and Guaraní and translated into Frenglish. Its rich and engaging multilingualism is just one dimension of its interest in identity and crossing (there are also genders, genres, and narratives at play). As always, Moure closely collaborates with the work she translates. When I first read the opening section “AVIS” (“bird,” “omen”; as well as aviso, “notice”, “warning”), I mistook it for a translator’s note, so uncannily Moure is Moure’s Bueno, and so fundamentally translational is Bueno’s voice. In this book, the author is not “one” but rather, “single seule sui-cide,” a killing of one self, of the single, self-same.

The story opens with a claim of identity, which is not so simple. “I am the catin trollop of this beach town, a marafona floozy.” Marafona is a word of Arab origin that can variously mean “whore,” “ragdoll,” “faceless doll.” Moure’s choices “catin” (“harlot”, “doll”; while “doll” would be slang in Bueno’s context for a trans woman) and “trollop” (“whore”; also, derives from “troll”) capture the richness of the term, the pleasure and shame invoked by it. From the beginning, the narrator’s gender eludes definition, and her body is a site of her own scrutiny and speculation: “the face I see in the miroir, is a face something close to those cubist paintings [. . .] the living stain of a visage that sees itself and still doesn’t understand a thing” (35).

The principle of the plot is uncertainty, like a whole Rashomon squeezed into one con-fused testimony. As the marafona’s confessions and non-confessions cross-write the story, far more interesting than “what (really) happened” are the fascinations of an interpretive universe in which contradictions pile up. I love how this piling, rather than feel futile or overwhelming-in-a-bad-way, pulls us closer to the language. Death and rebirth, gods and gobs, seafoam and formaldehyde, faits [“facts”] and fates are hopelessly tied together in a “tangle web webtangle” of Paraguayan lace. The story moves like a telenovela, as one sudden revelation upturns another, as the marafona swings from guilt to shame, tenderness, and power—and I am rapt. But again, the real drama is the language/s, how it twists to permit so much contradiction.

I read this book as virtuosic ode to ambiguity, multiplicity. The more the same thing multiplies, the more its singularity recedes. And, the more polychromatic (to capture a secondary denotation of the Guaraní word for “sea”) our seeing, our reading, becomes.

Writings

Waiting Room

How do you prefer to wait?

Scent of lactation and white that blues when wet. A wall of fish, somber flashing. My gaze freezes to glass, like fish, blazing gray, wrap in wax paper.

Is this your current address?

Placiest places I can muster. Garbled metal and kitchen lichen. Pretend it’s the house of a stranger: so much sieve, so much hard preparatory scan, under the pucker of bladed stars. What to kiss first? I’m naked as a rock or the bark of a tiny dog. In a dead man’s dress shirt, a child’s smock. Kids play, and later, there’s egg in the grass, sticky, tackled into a knot.

What are you waiting for?

Find a point that rots as you watch it. A hotel to visit, a harbor, stars. What a barrel of ice. What a sad white napkin of Asti Spumonte. I’d make a stupid bustier on the hotel ghost tour. I want to stay in the room wrapped in the lace of spontaneously waiting. It’s okay, I’m only playing. It took me weeks to freeze all these layers. Find a point and toy with it, torture it. Here lies Poe, the unhappy, in the ditch of his own proclivities. In this dereliction of the sea.

Is this your signature?

Red when cut is white. At least that’s how I think of poison. A face, powdered down to a distant likeness, then bright lipstick. I answer the front door. Fall mums, flowering brown and bitten. The whole yard watered too hard, so now it peddles death. Now it fruits dirt. In a red apple, a white bite hungry for my mouth.

Any new symptoms?

No birdbath, no birthing trough, but feathers and muzzles bloom. Poetically, I’m plucking the clock clenched in my knees. Please stop watching me cook. Wait, there’s no meat under the feathers. Please pick meatier flowers. Domestically, I am peering over a miniature. An oval mirror in a kindly iron frame. I hold it like an egg on a spoon. Keep it cold, so it will never hatch. Lift it to my ear and hear.

Providence

The rising sun freezes for a moment right where seeing ends. Forces its soft bright body through the bars on my window. My window when I was twenty. Under the bed that the last tenant left, a box of photographs, black and white, intimate. Shadows of what I thought might be—the guts, hand, heart, genitals of a person there before me, a figure knitted in wool, enclosed in silk, split into parts. Why bother to identify, I thought. The sun is a body, foreign as you are, in a box on the corner of Hope and Thayer. Now it’s morning again, blood in your eye from the other night, and all the crying. What is the last thing you remember? Iron bars cutting a sullen line against the sun.

Confluence, PA, 1952

How to communicate with your shadow, which shifts though you are still. Especially in water, with all its illegible gestures. She is nine or ten—bare chest, shaded face. With her posture, she’ll be a dancer, she’ll move through space as if enhancing the balance between everything she is and isn’t. That is the nature of movement. She stands in the river, her face barely visible, or chiseled by the invisible. You are invisible when you look down. Still as an unreturned gaze. That is the wound, the stillness of all that isn’t shown. And how passive is the human form in space.

Michelle Gil-Montero is a poet and translator of contemporary Latin American poetry and criticism. Her recent translations include Berlin Interlude (Black Square Editions, 2021) and Exilium (Ugly Duckling Presse, 2023) by Argentine writer María Negroni. She is the author of Object Permanence (Ornithopter Press) and the chapbook Attached Houses (Brooklyn Arts Press), and her writing has appeared recently in Interim Poetics, Spoon River Poetry Review, Black Sun Lit, Figure 1, Poem-A-Day, and other publications. She lives in Pittsburgh, teaches at Saint Vincent College, and runs the poetry-in-translation micropress Eulalia Books (eulaliabooks.com).

Michelle was recommended by Abigail Chabitnoy.